Lost Voices of Erddig: A Secret Harpsichord

In 1769, 15-year-old Anne Jemima Yorke ordered a harpsichord from the famous London maker Jacob Kirkman. A few months later, it was delivered to her home at Erddig, near Wrexham in North Wales. Though her mother Dorothy and older brother Philip, heir to the estate, supported Anne Jemima’s musical enthusiasm, the family was financially dependent on her wealthy uncle. They conspired to keep the expenditure a secret, fearing that her uncle would consider Anne Jemima’s purchase as an extravagant luxury. This project reveals the story of Anne Jemima’s harpsichord through a minidocumentary and a series of performance films, using scores drawn from her sole remaining music book and an outstanding historical harpsichord by Kirkman—the same model as her own, now vanished, instrument. Her story illustrates the significance of women and young people to developments in the music industry and to country house history in the eighteenth century.

In 1769, 15-year-old Anne Jemima Yorke ordered a harpsichord from the famous London maker Jacob Kirkman. A few months later, it was delivered to her home at Erddig, near Wrexham in North Wales. Though her mother Dorothy and older brother Philip, heir to the estate, supported Anne Jemima’s musical enthusiasm, the family was financially dependent on her wealthy uncle. They conspired to keep the expenditure a secret, fearing that her uncle would consider Anne Jemima’s purchase as an extravagant luxury. This project reveals the story of Anne Jemima’s harpsichord through a minidocumentary and a series of performance films, using scores drawn from her sole remaining music book and an outstanding historical harpsichord by Kirkman—the same model as her own, now vanished, instrument. Her story illustrates the significance of women and young people to developments in the music industry and to country house history in the eighteenth century.

Anne Jemima’s story emerged during research for ‘Music, Home and Heritage: Sounding the Domestic in Georgian Britain’, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council of Great Britain and led by Jeanice Brooks (University of Southampton) and Wiebke Thormählen (Royal College of Music). The rich musical history of Erddig, today managed by the National Trust, has been a major focus of the project.

Built in the late 17th century, the house was acquired by the Yorke family in 1733 when Simon Yorke I inherited the estate from his uncle John Meller. When Simon died in 1767, he was survived by his widow Dorothy, son Philip and daughter Anne Jemima. Philip (born 1743), was more than a decade older than Anne Jemima (born 1754). He had attended Eton and then, from 1762, completed his education at Cambridge before being called to the Bar in London. Around the time of his father’s death and his inheritance of Erddig in 1767, Philip had fallen in love with Elizabeth Cust, sister of his best friend at Cambridge, Brownlow Cust, and daughter of Sir John Cust of Belton House, Speaker of the House of Commons.

The Yorke family fortunes were at a low ebb, and the development of the Erddig estate and Philip's ability to marry were contingent on receiving an inheritance from his childless uncle James Hutton, Dorothy's brother. Family correspondence in the Flintshire Record Office shows that Hutton was a difficult character, and for two years the Yorke family was on tenterhooks about the inheritance and worried about displeasing him. While Philip remained in London to keep an eye on Hutton, whose lifestyle led the family to fear the loss of his fortune, Dorothy struggled on at Erddig. Her letters to Philip describe the difficulties of managing a large Welsh estate, but also reveal the growth of Anne Jemima’s musical interests.

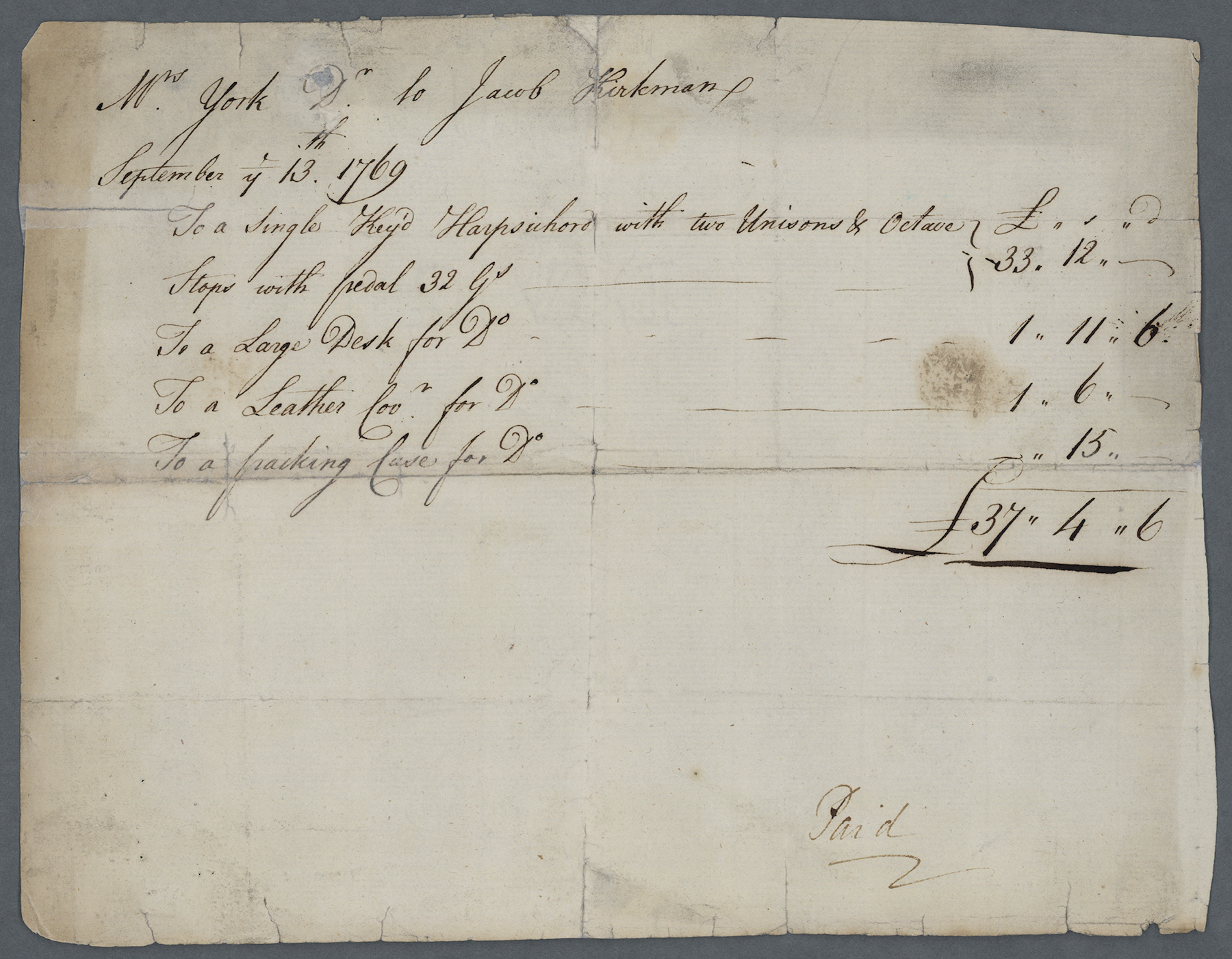

Anne Jemima took keyboard lessons from a Mr Gerard, likely the John Gerard who appears in some records as the organist of Wrexham Parish Church and who was a member of the Gerard family of organists associated with St. Asaph’s Cathedral and Bangor Cathedral in the 18th century. She had lessons every fortnight, and in between, as her mother recounts in a 1768 letter to Philip, she spent her time “strumming hard on the spinett.” Shortly afterward, Anne Jemima herself wrote to say she was worried that her uncle would find out how much money she was spending on music. Despite her concern, however, in June 1768 she wrote again with the tremendous news that she had ordered a new harpsichord—much more elaborate than her existing spinet—the last time Mr Gerard had visited. The instrument, from the premier London maker Jacob Kirkman, cost £37 pounds with its cover and case: an overwhelming proportion of her £50 allowance. Both Anne Jemima and Dorothy wrote to Philip immediately to let him know of the purchase, while at the same time urging him to conceal the order from his uncle.

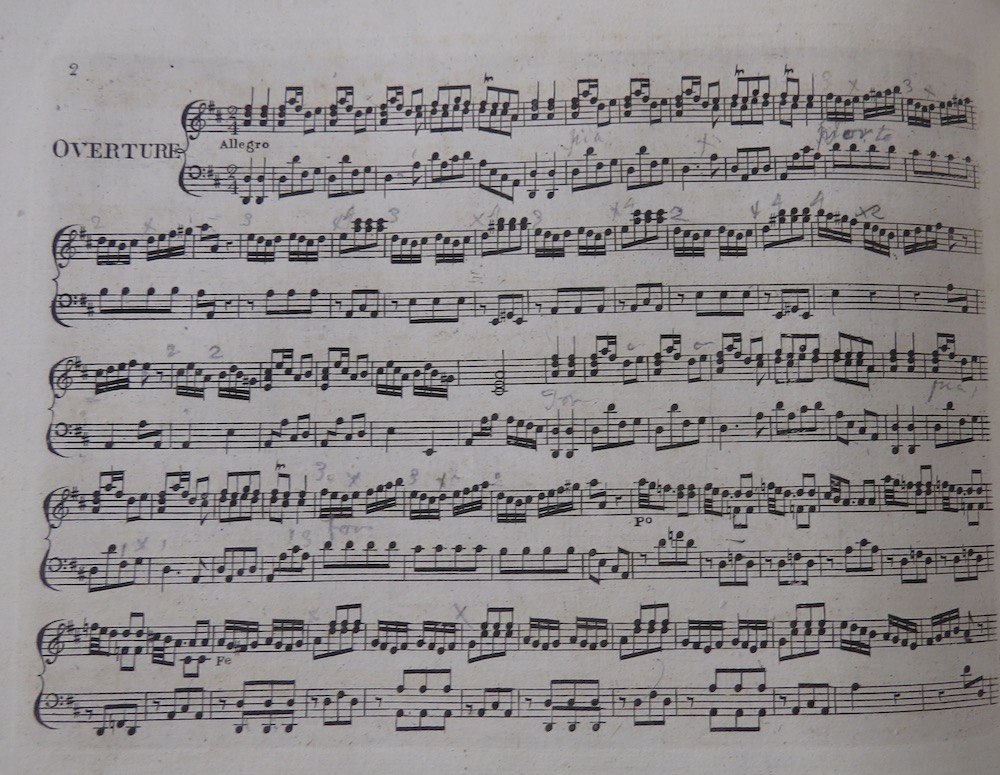

Anne Jemima’s harpsichord arrived at Erddig three months later. Her sole surviving music book provides some insight into what she played on it. Labelled “English Operas,” it includes scores for five stage works, most with librettos by Isaac Bickerstaff, that were hits of the London stage in the 1760s. In addition to the popular pastiches Lionel and Clarissa and The Maid of the Mill, Anne Jemima had scores of Midas (a burletta poking fun at serious opera); of Charles Burney’s arrangement of J.J. Rousseau’s Devin du village as The Cunning-Man; and of Charles Dibdin’s comedy The Padlock, in which the composer notoriously created the role of the West Indian servant Mungo. Her annotations, and those of her teacher, on the scores shows how she turned the songs from these shows into solo pieces for the harpsichord. All five scores were bound together in 1770, when Anne Jemima signed and dated the flyleaf of her opera album, still conserved at Erddig today.

Anne Jemima’s harpsichord arrived at Erddig three months later. Her sole surviving music book provides some insight into what she played on it. Labelled “English Operas,” it includes scores for five stage works, most with librettos by Isaac Bickerstaff, that were hits of the London stage in the 1760s. In addition to the popular pastiches Lionel and Clarissa and The Maid of the Mill, Anne Jemima had scores of Midas (a burletta poking fun at serious opera); of Charles Burney’s arrangement of J.J. Rousseau’s Devin du village as The Cunning-Man; and of Charles Dibdin’s comedy The Padlock, in which the composer notoriously created the role of the West Indian servant Mungo. Her annotations, and those of her teacher, on the scores shows how she turned the songs from these shows into solo pieces for the harpsichord. All five scores were bound together in 1770, when Anne Jemima signed and dated the flyleaf of her opera album, still conserved at Erddig today.

Anne Jemima’s death that same year, aged only sixteen, replaced the sounds of her harpsichord with those of mourning. The harpsichord itself remained at Erddig for many years, and tuning and maintenance records suggest it was used by her brother Philip’s family into the nineteenth century. By 1835, however, it had been replaced by a newer piano, and an inventory of that year shows it was stored, unused, on an upstairs landing; afterwards, there is no further trace of its fate. Its replacement and eventual disposal marked a major change in the domestic soundscape of Erddig.

Anne Jemima’s story highlights the importance of girls and young women to the history of both music and the country house in the eighteenth century. Teenage girls were a major driver in the expansion of the British instrument building trade, which both reflected and shaped their activities and tastes. In producing performances at home, domestic performers like Anne Jemima not  only played an important role in the economics of the burgeoning music publishing trade in Britain. They also disseminated repertoires, acting as crucial agents by taking theatrical music to regions and contexts beyond the stage. A focus on Anne Jemima also provides new perspectives within a country house historiography that still often focusses on male owners and architects. Recent research by historians of material culture, however, emphasises how women contributed to both the construction and décor of British country houses. Considering both the material and sounding aspects of music as a factor in the domestic interior and its soundscape shows how teenage girls were also part of the creation of the country house in the 18th century.

only played an important role in the economics of the burgeoning music publishing trade in Britain. They also disseminated repertoires, acting as crucial agents by taking theatrical music to regions and contexts beyond the stage. A focus on Anne Jemima also provides new perspectives within a country house historiography that still often focusses on male owners and architects. Recent research by historians of material culture, however, emphasises how women contributed to both the construction and décor of British country houses. Considering both the material and sounding aspects of music as a factor in the domestic interior and its soundscape shows how teenage girls were also part of the creation of the country house in the 18th century.

The minidocumentary below delves further into Anne Jemima’s story, considering the sound and construction of her harpsichord and exploring her performance of music from the London stage. Although Anne Jemima’s own harpsichord has vanished, an outstanding Kirkman instrument of exactly the same model, which was built in 1766 just three years before her own, was kindly loaned for the project. This harpsichord stars in a further set of films made with harpsichordist Magdalena Jones, linked in the Video Galleries page, which focus on repertoire from Anne Jemima’s book of London operas and on other eighteenth-century music from Erddig that she would have known.